The natural history of a viral infection is the outcome of virus/host interactions at three levels:

- the interaction of the virus with its host cell

- the nature of the response of the infected individual to infection

- the source of virus and route of transmission in the community

Effects of viruses on cells may be short term and lead to cell death within a few hours (e.g. poliovirus or influenza) or persist for the lifetime of the cell, either latent or capable of being reactivated by external stimuli (e.g. herpes viruses) or in defective form where, although incapable of replication, they may transform the cell into a malignant state (e.g. papillomaviruses).

Rubella is unusual in causing no obvious damage to cells in culture but significantly impairing the cells' ability to grow and divide. The specific cell type affected (or tissue tropism) also determines the pathogenic potential of a virus.

Symptoms of rubella - rash, fever, lymphadenopathy and arthropathy are due to the host response to infection.

As virus is released from infected cells, antibody is produced and forms virus/antibody complexes which are deposited from the circulation into the skin and joints where their presence stimulates the production of cytokines which are the cause of symptoms. The patient's recovery and the elimination of the virus from the body are achieved by destruction of the infected cell remnants by activated lymphocytes, coupled with the presence of antibody, which neutralises any extracellular virus before it can enter a new host cell.

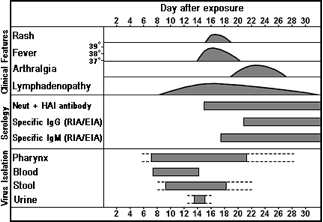

The time course of events is portrayed in a pathogenesis diagram that shows the route of infection and the infective dose The extent of virus growth in tissues and the rate of specific antibody and CMI responses are shown in relation to the patients symptoms and concurrent tissue pathology. It also indicates the duration and route(s) of virus excretion and the generation and persistence of subsequent immunity.

Clinical Features and virological markers of acute rubella infection

This diagram portrays infection in an immune competent individual, but the important clinical effects of many virus infections occur in immature or immune suppressed patients. The infection may then be prolonged and the virus replication may reach much higher levels with more severe tissue damage. Rubella infection during the first few weeks of gestation produces extremely severe growth retardation in the most rapidly developing tissues and prediction of the outcome of infection can be made on the basis of this information.

The epidemiology of an infectious disease is defined in terms of who, when and where it occurs.

This may be measured clinically (as cases notified to the health department by their doctor) or seroprevalence of infection (antibody surveys). The age at which infection commonly occurs, the seasonal and year to year variation, and recognition of regions of high prevalence that might be related to a non-human source, are all significant in constructing a picture of how a virus spreads and how it is maintained in the community.

Intermittent (epidemic) patterns are usually produced by agents that are readily transmitted and cause acute disease, followed by long term immunity in survivors.

A new epidemic can only occur once a new population of susceptible individuals(e.g. a new generation of children) is available, or a new strain of the virus with different antigenic structure emerges (e.g. influenza). Epidemics also arise when an infection is introduced to a population where it was previously unknown (e.g. HIV).

Constant (endemic) patterns occur with viruses that are excreted by "carriers" long after their acute infection has subsided (e.g. glandular fever), or with infections that confer little or no long term immunity (e.g. gonorrhoea).

Strategies to combat an infectious disease depend on assessment of all three elements of the natural history. Some infections are readily controlled by interruption of the route of transmission (e.g. cholera via clean water supply), others by recognising and treating active cases of disease (e.g. TB, syphilis). For virus diseases such as rubella, vaccination of the susceptible population is the main avenue of prevention.

Associated learning topic

References

Burgess MA. Gregg's rubella legacy 1941 -1991. MJA 1991, 155(6):355-7

Menser MA, Hudson JR, Murphy AM, Upfold LJ. Epidemiology of congenital rubella and results of rubella vaccination in Australia. Rev Infect Dis 1984; 7(Suppl. 1): S37-S41